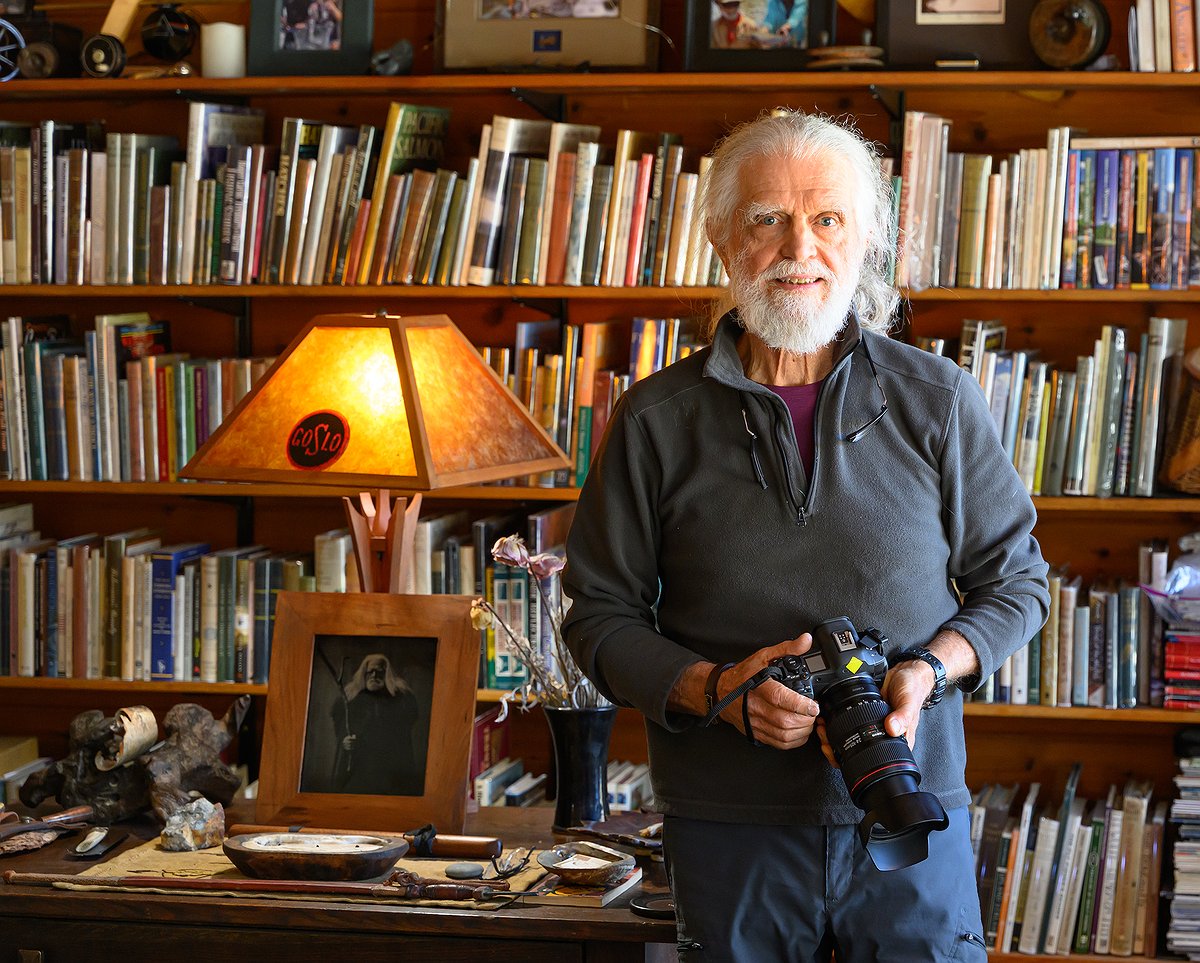

Lee’s vision: West Glacier man does striking portrait project of valley homeless people

Lee Jester has always had an eye for photography. When he was a senior in high school, he took all the photos for the yearbook.

“Every kid got a full page,” he recalled.

Having said that, there were only 20 kids in the class. Jester went to a boarding school in Switzerland, while his father sold oil refineries to Arabs, he said.

He started out with Rollei twin lens reflex camera and an Exacta, which was “built like a tank.” They were film cameras, of course.

But photography over the years came and went, he admits.

“I had several cameras stolen,” he said. “That cramped my act.”

It was the 1960s and Jester was a hippie, he said. He owned what he could carry in a suitcase. But he did eventually work in the professional world as antique and book dealer in Berkeley, California.

He also became an avid fly fisherman and about 20 years ago, he started looking for a place to retire and found a home outside of Glacier National Park in West Glacier along the banks of the Middle Fork of the Flathead River.

At 76, he fly fishes four or five times a week. He only has to walk about 50 yards to the river across a gravel bed to wet a line.

Over the years he’s collected about 1,000 books on fly fishing and he’s very active in Trout Unlimited. That interest in conservation resulted in a series of portraits he took of the “conservation elders” of Montana — people who were founders of the movement in the state.

“I went to wherever they were,” he said. “They would barely sit for me.”

But then the pandemic hit and he couldn’t visit with them anymore. Meanwhile, some of them died as well. In February he did another cool project where he photographed guests at the Flathead Warming Center in Kalispell.

Jester admits he experienced homelessness in his younger days and he took pains to not exploit the individuals he photographed. Every one who agreed to be photographed was paid $20 and, in turn, they signed releases to use their photos.

The photos were taken with a Canon digital camera and converted to black and white digitally.

He’s now working on a project to make a documentary out of a book by the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribe called “The Bull Trout’s Gifts.”

He hopes to produce the film with help from the tribe and is in talks with film crews from Missoula.

He has a special place in his heart for the endangered fish. He caught a big bull trout in the Bob Marshall after it came up and ate a small cutthroat trout that he hooked on his three-weight fly rod. The bull, which was more than 30 inches long sulked under a rock, then sped off with his line. He eventually landed the fish after three runs.

A friend just happened to walk up out of the blue with a net and a camera and snapped his picture with the trout before he released it.

Jester smiles as he looks at the picture.

“I’m kind of a crazy old man,” he said.